For some turfgrass species in Georgia, Microdochium patch can become problematic when nighttime temperatures dip to 32–46 °F (0–8 °C) with high relative humidity. The disease is most prevalent in turfgrasses mowed lower than 0.5 in. (1.25 cm), such as putting greens, fairways, and sports fields. The disease can be severe on annual ryegrass, perennial ryegrass, or tall fescue but also can infect warm-season grasses such as bermudagrass and seashore paspalum if they are actively growing in the fall or if they are semidormant.

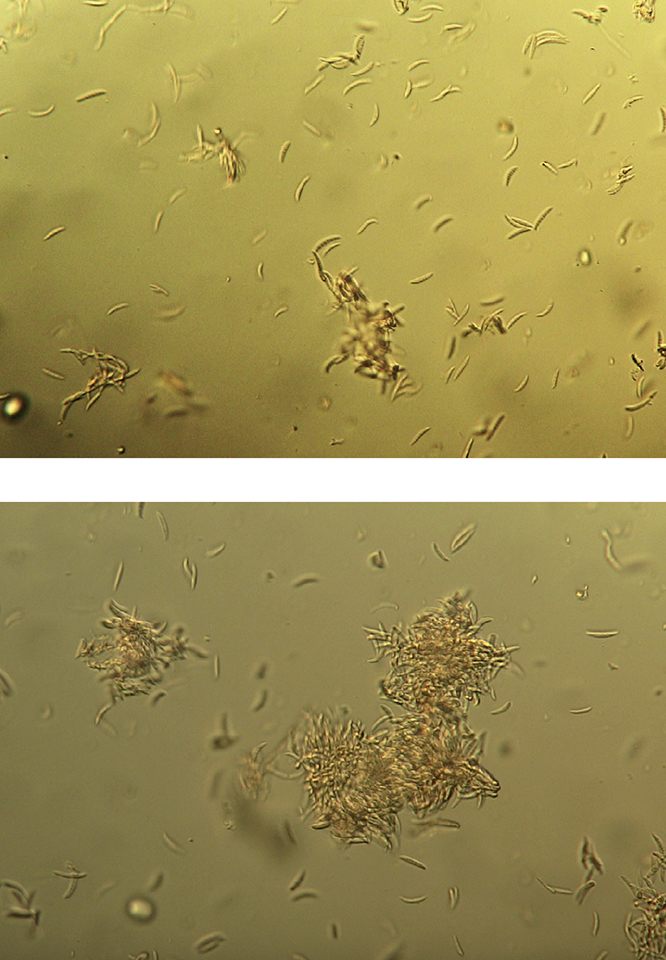

Figure 1. Asexual spores (conidia) of Microdochium under a compound microscope.

Photos: A. Martínez

The Pathogen

The causal organism for Microdochium patch has been reclassified from the genus Fusarium to the genus Microdochium using molecular taxonomic techniques. There has been debate about whether the common name, “pink snow mold,” is a satisfactory description because the disease appears pink only in certain conditions and the disease is not limited to snow-covered turf. In Georgia, the disease appears without snow cover. Now it is widely accepted that “Microdochium patch” is caused by Microdochium nivale (syn. Monographella nivalis; Figure 1). Other fungi often are associated with M. nivale, including F. culmorum, F. equiseti, F. avenaceum, and F. semitectum, all of which infect grasses at low temperatures.

Symptoms

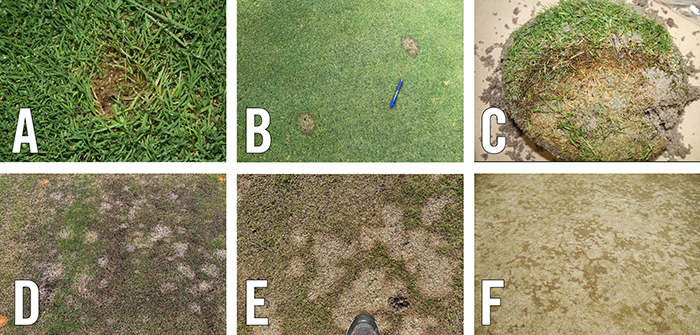

Infections start as small, water-soaked spots of less than 2 in. (5 cm) in diameter (Figure 2A) that rapidly change in color from orange to brown to light gray or tan. The spots grow or coalesce to form bigger patches of more than 8–9 in. (20 cm) in diameter (Figures 2B, 2C, and 2D) with a burnt appearance. The outer perimeter of the patch may have a brown, dark margin. If the conditions are conducive for pathogen infection—cold, overcast, wet conditions—a thin, fluffy mycelium can be observed on affected leaves, which can be confused with a Pythium or dollar spot infection. In Georgia it is not uncommon to see Microdochium patch on quasi-dormant bermudagrass or seashore paspalum (Figures 2E and 2F).

Figure 2. Initial symptoms of Microdochium (Fusarium) appear as small yellowish, orange, or reddish spots (A). Advanced symptoms of Microdochium display a dark-brown-to-black ring (B and C) in the outer perimeter of the patch. Turf in the center of the patch is completely collapsed. Close-up of Microdochium (D) on seashore paspalum (Paspalum vaginatum) from an experimental plot in Griffin, GA. Microdochium patch on quasi-dormant seashore paspalum (E) and bermudagrass (F).

Photos: A. Artiaga and A. Martínez

Conditions Favoring Microdochium Patch

The disease occurs more frequently in late fall or early spring in Georgia when the temperatures oscillate between 32–46 °F (0–8 °C). This coincides with high relative humidity and reduced sunlight. Microdochium is more severe in turf with excessive thatch. High nitrogen fertility can increase the susceptibility of the turf to Microdochium. High mowing height, compact soils, and poor drainage all can contribute to the development of the disease. The disease tends to subside when temperatures are above 60 °F (16 °C), during sunny days, and when the canopy dries. Conidia (a fungus’ asexual spores) are ubiquitous, and infected plant residues are easily carried and spread on equipment wheels, mowers, irrigation, foot traffic, and animals.

Control

Avoid heavy or late-season applications of nitrogen and avoid forms of nitrogen that are readily soluble in water. Continue to mow into late fall to avoid excessive moisture lingering on the foliage, avoid excessive thatch accumulation, and prevent soil compaction. In early spring, promote rapid turf drying and warming by improving soil drainage and eliminating barriers to sunlight. Low soil pH and the maintenance of balanced soil fertility also help to control the disease.

In Georgia, fungicides and premixed fungicide products that are effective against Microdochium contain one or more of these active ingredients: azoxystrobin, fluoxastrobin, fluxapyroxad, iprodione, metconazole, propiconazole, pydiflumetofen, pyraclostrobin, thiophanate-methyl, triadimefon, trifloxystrobin, triticonazole, and/or vinclozolin. For a complete and updated list of available fungicide products, refer to the latest edition of 海角官方首页 Extension Bulletin 984, Turfgrass Pest Control Recommendations for Professionals. Various publications on turfgrass pests are available on the turfgrass website:

References

Butler, L., & Kerns, J. (2019). Microdochium patch in turf. North Carolina State Extension.

Downer, A. J., & Harivandi, M. A. (2009). Microdochium patch (Fusarium patch, pink snow mold). University of California Cooperative Extension.

Smiley, R. W., Dernoeden, P. H., & Clarke, B. B. (2005). Compendium of turfgrass diseases (3rd ed.). American Phytopathological Society.

Status and Revision History

Published on Mar 30, 2010

Published with Major Revisions on Dec 01, 2012

Published with Minor Revisions on Apr 18, 2017

Published with Minor Revisions on Oct 28, 2024