The term natural enemy comes from the study of biological control or the control of pests by living organisms that regulate pest populations. A natural enemy could eat the pest (predator), live inside of the pest until development is complete (parasitoid), or cause infection in the pest population (pathogens). Natural enemies of pests are valuable to crop production and can help with pest control. Having a diversity of natural enemies and types of natural enemies in a system helps with regulating multiple pest species.

A challenge for modern agriculture is providing the conditions to balance the demands of production with the promotion of natural enemies to provide biological control services. Knowing and recognizing naturally occurring predators and parasitoids is a first step. We provide a brief overview of common groups and then discuss habitat management concepts for conservation.

Common Native Predatory Natural Enemies

This section provides an overview of common predatory arthropod species (insects and spiders) in blueberry systems—including both the vegetation within blueberry fields and the border areas surrounding those fields—of the Southeast, based on information from Extension publications and our recent research in the primary blueberry-producing counties of Georgia (Whitehouse et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2019; Schmidt et al., 2021). For more detailed information, please read the referenced publications. Based on this research, we find that these communities of natural enemies currently are composed of many spiders, some insect predators, and few parasitoids.

Araneae: Spiders

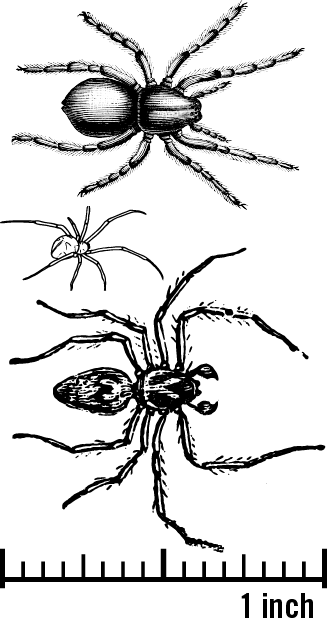

Figure 1. Scale and Relative Sizes of Various Life Stages of the Wolf Spider, Cobweb Weaver, and Lynx Spider. From top to bottom: a wolf spider, a cobweb weaver, and a lynx spider.

Figure 1. Scale and Relative Sizes of Various Life Stages of the Wolf Spider, Cobweb Weaver, and Lynx Spider. From top to bottom: a wolf spider, a cobweb weaver, and a lynx spider.

Adult spiders range in size from very small to very large. In addition, immature stages of different species range in size and appearance, making it very difficult to distinguish species at immature stages. Some spiders can produce up to 1000 or more eggs and offspring in one season. The functions of spiders in blueberry systems are not well studied, but some species build webs that capture a variety of mobile pests like flies, caterpillars, thrips, and aphids, and other species forage among the vegetation by ambushing prey or chasing them down. Figures 1 and 2 show both the size distribution of spiders and general forms of spiders to help you characterize them easily in the field. Notice that some of the spiders have appendages at the front, resembling additional legs or boxing gloves; these are male spiders. Spiders with thinner legs and smaller bodies often are web-building types, and larger-bodied spiders or those with thicker legs are more commonly found on the ground.

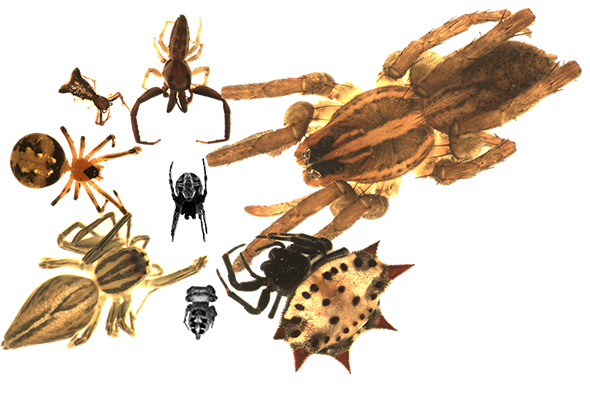

Figure 2. A Diversity of Spiders is Common in Blueberry Fields.

Clockwise from the top center, the families of common spiders represented are: Salticidae, Lycosidae, Araneidae, Salticidae, Oxyopidae, Theridiidae, Salticidae; center: Araneidae.

Neuroptera: Lacewings

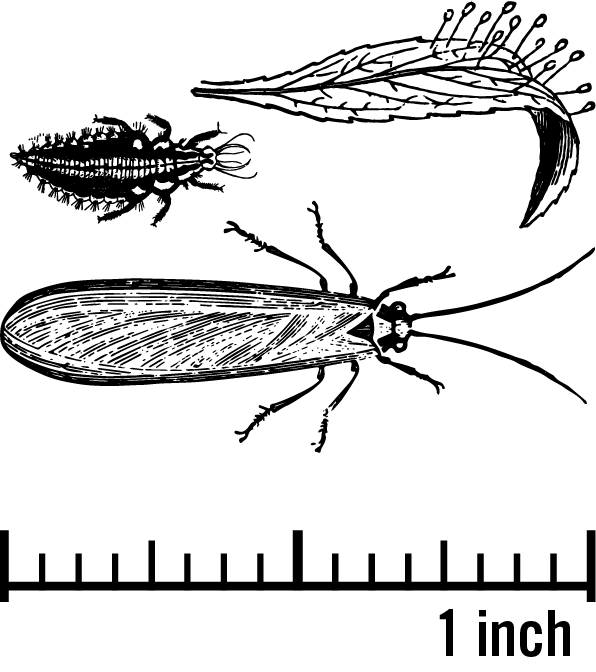

Figure 3. Scale and Relative Sizes of Various Life Stages of the Lacewing.

Figure 3. Scale and Relative Sizes of Various Life Stages of the Lacewing.

Lacewings are generalist predators of aphids, spider mites, scales, and other small insects. Their size distribution at various life stages is seen in Figure 3. These predators get their name from their thin translucent wings as adults (Figure 4A). The larvae have piercing-sucking mouthparts, and often are referred to as "alligators" (Figure 4B). Figure 4C shows the unique form of their eggs, which look like thin stalks with a ball at the end. These predators live diverse lifestyles. You can find eggs in both crop and noncrop areas. Larvae are voracious predators, while adults feed mostly on nectar and pollen.

Figure 4. (A) Lacewing Adult on a Leaf, (B) Lacewing Larvae or “Alligator,” (C) Lacewing Eggs on the Underside of a Leaf.

Photos (a-c): Melissa Schreiner, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org; Bradley Higbee, Paramount Farming, Bugwood.org; Brett Blaauw.

Hemiptera: True Bug Predators

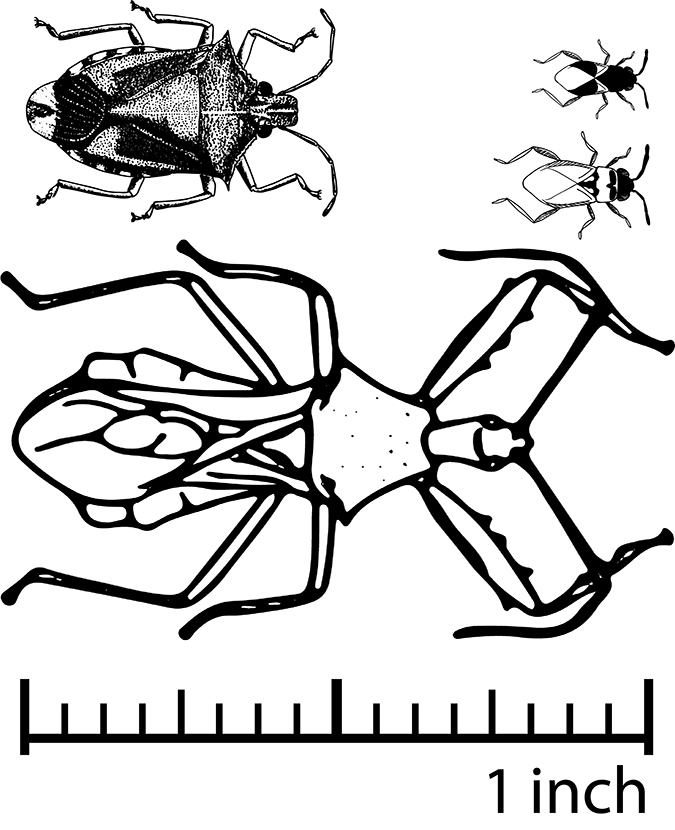

Figure 5. Scale of Hemiptera Bugs.

Figure 5. Scale of Hemiptera Bugs.

Predators in the Hemiptera order all have piercing-sucking mouthparts. Hemiptera suck the juices out of pest eggs, larvae, and/or adults. Most are generalist predators and feed on a variety of pest species, including Lepidoptera (winged insects) eggs and larvae, aphids, mites, white flies, and plant bugs. Some of the beneficial predaceous Hemiptera can be challenging to discriminate from pests, especially in their immature stages. Figure 5–9 show examples of a range of a few common predaceous Hemiptera, including their sizes and colors.

Figure 6. Assassin Bug Adults.

Photos: Russ Ottens, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

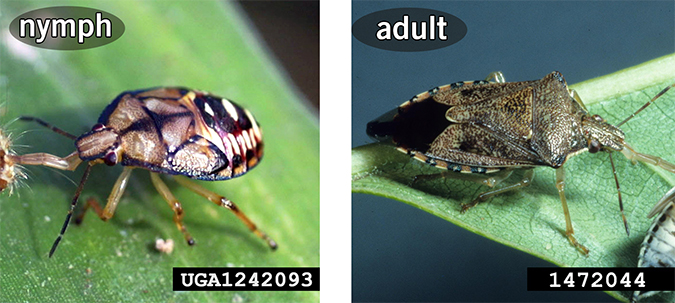

Figure 7. Spined Soldier Bugs in Nymph and Adult Stages.

Photos (left to right): Russ Ottens, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; Frank French, Georgia Southern University, Bugwood.org.

Figure 8. Big-Eyed Bugs in Nymph and Adult Stages.

Photos: Russ Ottens, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

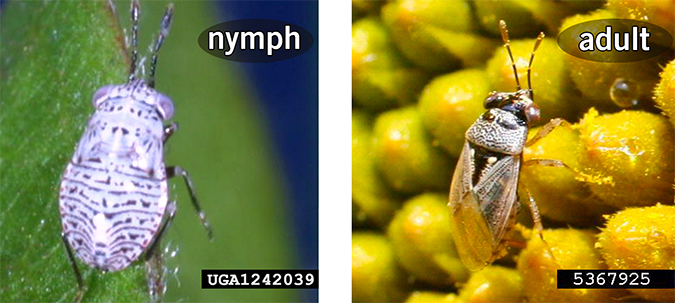

Figure 9. Minute Pirate Bugs in Nymph and Adult Stages.

Photos (left to right): Adam Sisson, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org; John Ruberson, Kansas State University, Bugwood.org.

Coleoptera: Ground Beetles and Rove Beetles

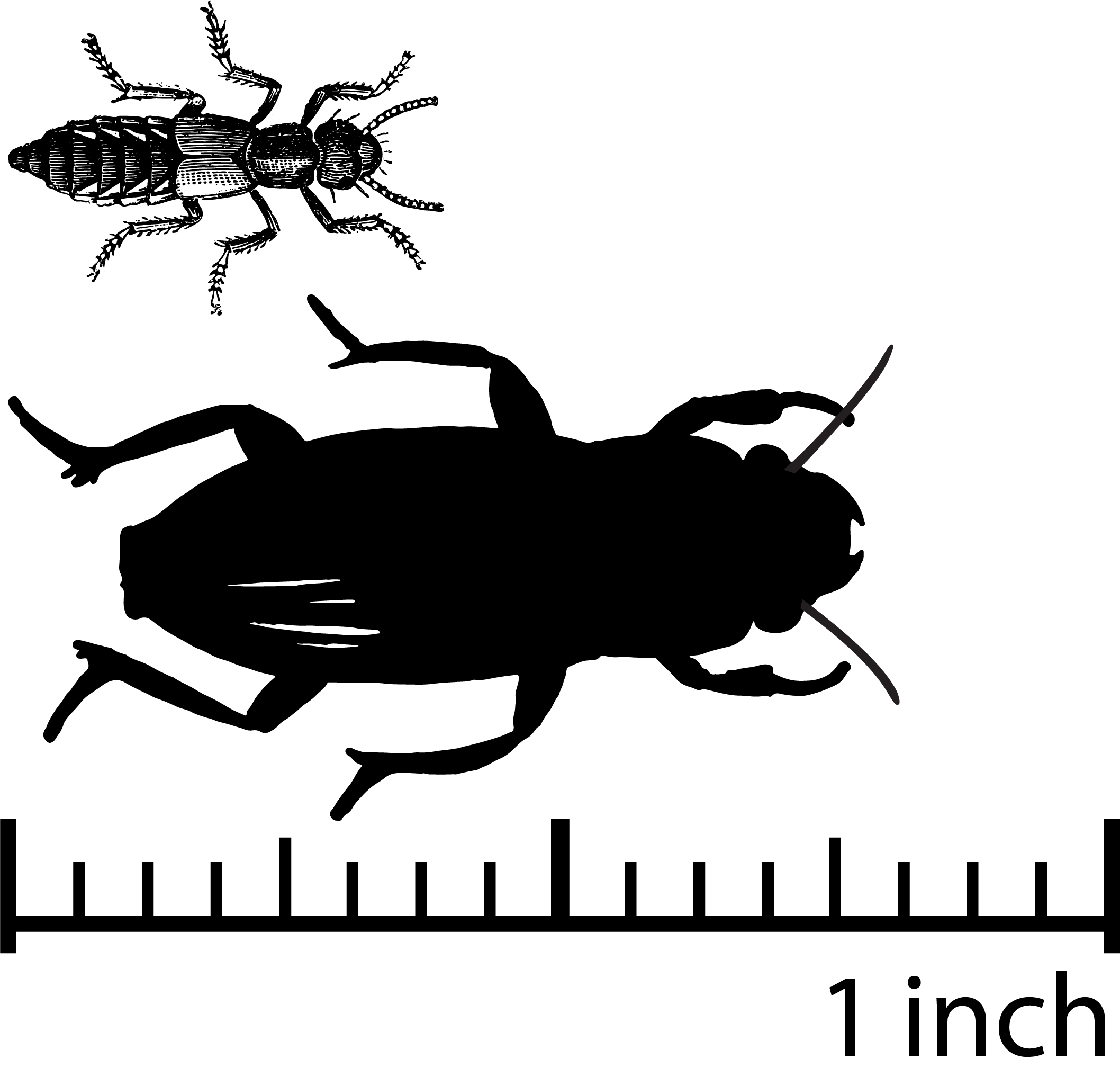

Figure 10. Scale of Coleoptera Beetles.

Figure 10. Scale of Coleoptera Beetles.

Coleoptera, the order of beetles, is one of the most diverse groups of animals on Earth. These beetles live in many habitats from lakes to crop systems, and on the shores of beaches foraging for insects, decaying material, and seeds. Beetles also are important as nutrient cyclers because they process the dung from vertebrates (Fuzessy et al., 2021). In blueberry systems in Maine, dung beetles potentially reduce disease in blueberries (Peterson, n.d.). Figures 11–12 show a few examples of ground predators and scavenging predators that can be found both on the ground and in the canopy. The rove beetles, or Staphylinidae, occur on the ground but also forage in flowers and vegetation. Some of these predators eat both prey and weed seeds. Our coverage here is limited in scope by what we've observed and reported in recent extension articles. Given the diversity of Coleoptera, there are likely many more to be found.

Figure 11. Adult Stage of Various Ground Beetles.

Photos (left to right): Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org; Jessica Louque and Smithers Viscient, Bugwood.org.

Figure 12. Adult Stage of Rove Beetles.

Photos (left to right): Joseph Berger, Bugwood.org; Merle Shepard, Gerald R.Carner, and P.A.C Ooi, Insects and their Natural Enemies Associated with Vegetables and Soybean in Southeast Asia, Bugwood.org.

Coleoptera: Coccinellidae (family), a.k.a., Lady Beetles

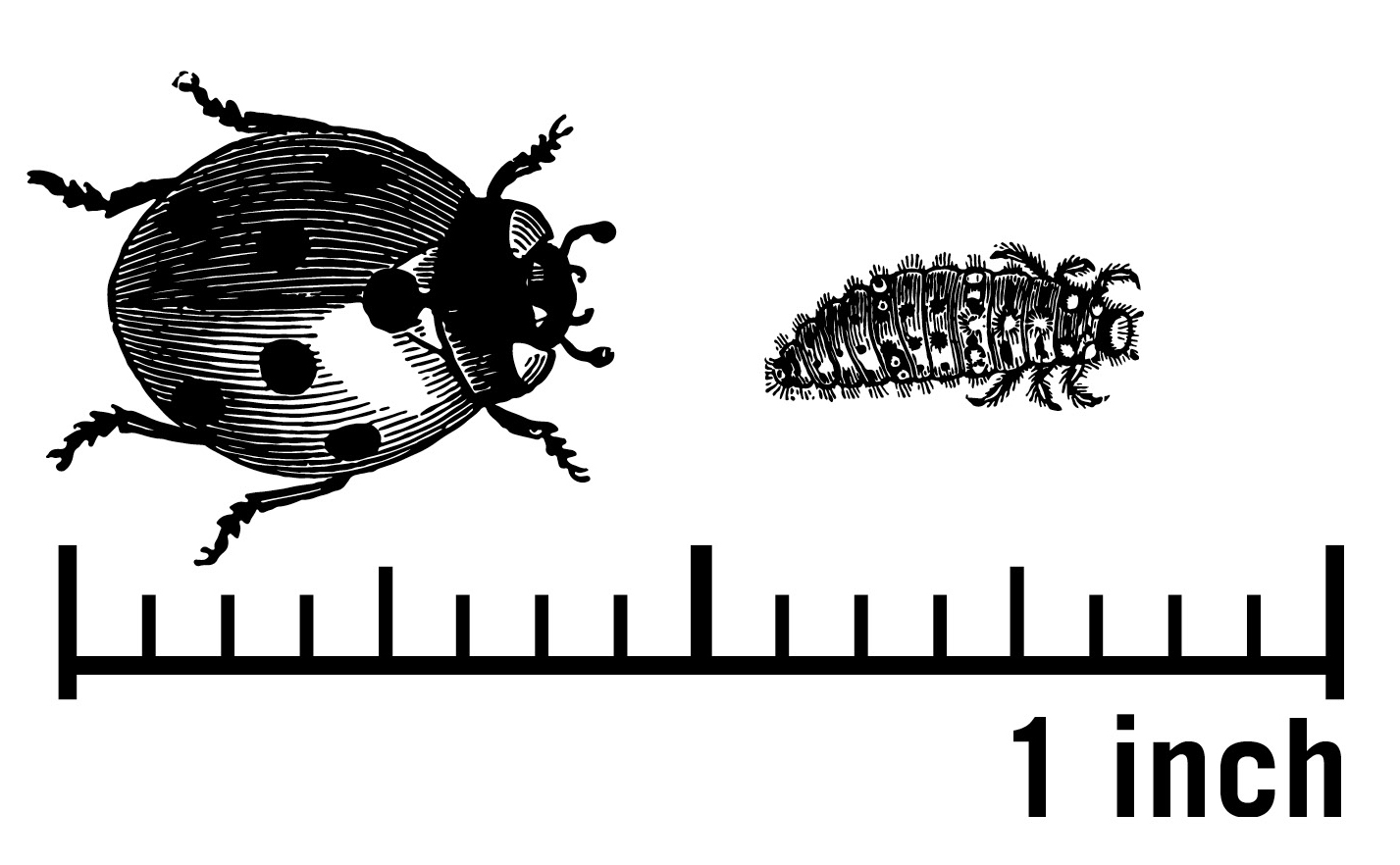

Figure 13. Scale of Coleoptera: Coccinellidae.

Figure 13. Scale of Coleoptera: Coccinellidae.

Predators in the family Coccinellidae are the iconic "ladybugs" that we often think of as predators. Ladybug species range in size (about 2 to 10 mm) but are not as variable as hemipteran predators or spiders (Figure 13). The smallest (Scymnus sp.) appear quite different as their larva are covered in white waxy strands (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Scymnus sp. Larvae and Adult.

Photos (left to right): Bodie Pennisi; Jim Jasinski, Ohio State University Extension, Bugwood.org

While known for predation on aphids, ladybugs also eat a range of pest types, including aphids, caterpillar eggs, and spider mites. They also use pollen and nectar as supplemental food sources. Unlike the hemipteran predators, ladybugs develop from eggs to larvae, then pupate into adults (Figure 15). Be on the lookout for mostly yellow- or orange-colored eggs, sometimes as many as 100 eggs on a leaf. Larvae often are black and yellow but vary and some are waxy-looking or spiky-looking (Figure 15B). Adults vary in color and size; learn more about their color diversity, sizes, and ladybug forms in Tomaszewska et al. (2021). The size scale provided in Figure 13 is for larger ladybugs such as the seven-spotted ladybug and the multicolored Asian lady beetle. Other species are smaller.

Figure 15. (A) Lady Beetle Eggs, (B) Lady Beetle Larvae, (C) Pupae Lady Beetle, (D) Adult Lady Beetle

Photos: A: Bodie Pennisi; B: Susan Ellis, Bugwood.org; C–D: Louis Tedders, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org.

Other Flying Predators: Diptera and Hymenoptera